Friday, December 10, 2010

Good to Think

Wednesday, December 8, 2010

Is There Science Behind the Medieval Allegorical View of Animals?

The Wolf: A Villain or Victim?

Although it is impossible to recreate models with sufficient evidence to satisfy modern ecologists, data suggests, “comparable multi-prey systems appear to have existed in medieval northern Europe” (Pluskowski). In other words, wolves in the Middle Ages preyed on the same animals as wolves today. Thus, for the most part, wolves in the Middle Ages hunted animals like deer, sheep, and dogs. However, unlike today, where people rarely come in contact with wolves, wolves were perceived to be a threat to humans in medieval Britain and Scandinavia. As Pluskowski writes, people in these areas during the Middle Ages feared the wolf and “attacks likely rose from the early to high medieval period…on the basis that people continued to encroach on the wolves habitat and had more frequent contact.” However, the article does hedge this statement by saying that while there are references to people being angry at wolves for harming people and animals, there are few documented accounts of attacks. Therefore, it is hard to distinguish from records whether people’s fear of wolves in the Middle Ages was valid.

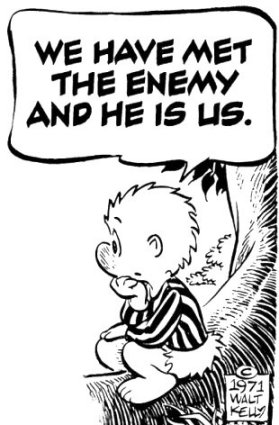

We Have Met The Enemy And He Is Us

Final Thoughts

Sexing Species

EP

Tuesday, December 7, 2010

Animals as comfort

Now, my newborn niece very recently died with no medical explanation (yet) and everyone in my family is taking it fairly hard (of course!- we tend to think this stuff doesnt happen anymore but it does). 3 days ago, my mom's boss brought in pictures of a litter of puppies her dog just gave birth to and sure enough, my parents just got a new puppy and have already started shopping for things for the puppy and they haven't even brought him home yet (he's still too young). She claims that they were just too cute to resist. Now admittedly the puppy is definitely adorable (very few arent) but I doubt my parents would have chosen to get another dog if they weren't hurting from Hailey's death.

Not all animals have to have a use. sometimes they just bring comfort and companionship, even in the Middle Ages: not all dogs were hunting dogs, not all cats were barn cats, not all birds were songbirds or falcons. Childhood death (and death in general) was much more common in the middle ages but certainly not any easier to handle and i wonder how often people turned to animals as a source of comfort. Its not something that there would be much in the way of documentation or evidence for but people's emotional needs have remained the same throughout recorded history so I have a feeling that it happened plenty.

Just a thought.

LRW

Monday, December 6, 2010

Some Wondrous Final Thoughts

The book chronicles the shifting form of "the mysterious" throughout western culture -- very often in the form of mythical beasts from faraway lands. The concept of wonder is located in an immense semantic field populated by many related terms that also have unstable and changing meanings: marvels, miracles, monsters, prodigies, curiosities, and relics.

Yet, the approach modifies the conventional story only expanding horizons beyond professional scientific practice throughout the Middle Ages and shows how, "The quiet exit of demons from theology coincides in time and corresponds in structure almost exactly with the disappearance of the preternatural in respectable natural philosophy" (361). Essentially, the work argues that a section of European population evolved psychologically from a culture dominated by superstition and Church doctrine, where mystery was an everyday theme, to one that placed a certain value on the unknown - eventually leading to the beginnings of modern science. Science is usually accused of having destroyed wonder, but Daston and Park reject this view, and purport it almost as an intermediary between superstition and science.

One choice quote I used for my paper to illustrate this point is from Marco Polo, as he describes the kingdom of Quilon:

"The country produces a diversity of beasts different from those of the rest of the world. There are black lions with no other visible color or marks. There are parrots of many kinds. Some are entirely white – as white as snow – with feet and beaks of scarlet. Others are scarlet and blue – there is no lovelier sight than these in the world. And there are some very tiny ones, which are also object of great beauty. Then there are peacocks of another sort than ours and much bigger and handsomer, and hen too that are unlike ours. What more need I say? Everything there is different from what it is with us and excels both in size and beauty."

This makes me wonder (no pun intended) if the shift from attaching symbolic and religious importance to the mysterious (ie: bestiaries) to the celebration of such things indeed indicates a shift in the medieval consciousness -- or, perhaps that's too enormous a claim to make.

Either way, I find it interesting that the same medieval society, or at least some portion of it, took interest in the "strange" animals from overseas without overtly questioning or attaching religious/supersticious implications to them. Is this human progress? Or is it too simplistic to say that curiosity necessarily trumps superstition in this linear manner?

Still, the culture of the early middle ages is not without its wonders -- the fact that the unicorn was chronicled alongside bears and dogs should be proof enough of that. Which makes me realize that the belief is the mysterious, the odd, and the unknown, even given it's shifting forms, persists today. Take P.T. Barnum's grotesque legacy of the traveling freak show for example, or (god forbid you ever watch it!) the History Channel's program on "Ancient Aliens." So when it comes to wonderment, it's unlikely we will ever stop finding it tempting to, "believe it," as Ripley says, "or not."

-TJB

Daston, Lorraine, and Park, Katherine. Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150-1750. New York: Zone Books, 1998.

Sunday, December 5, 2010

Power, Status, and Symbolism: A Final Look

Friday, December 3, 2010

Parting Thoughts and Dogs in Heaven

Dan F

Basil, Beasts, and the Contemplation of Nature

It is said that the vultures hatched without coition a very great number of young, and this, although they are especially long-lived; in fact, their life generally continues for a hundred years. Consider this as my special observation from the history of birds, in order that, if ever you see any persons laughing at out mystery, as though it were impossible and contrary to nature for a virgin to give birth while her virginity itself was preserved immaculate, you may consider that God...first set forth innumerable reasons from nature for our beliefs in His wonders.4

The ox is steadfast, the ass sluggish; the horse burns with desire for the mare; the wolf is untamable and the fox crafty; the deer is timid, the ant industrious; the dog is grateful and constant in friendship.5

No skill in gathering roots or acquaintance with herbs procured for the irrational animals the knowledge of what was useful, but each of the animals is able naturally provisions for its own safety and it posses a certain inexplainable attraction toward what which is according to its natures. We also possess natural virtues toward which there is an attraction of soul not from the teaching of men, but from nature itself...If the lioness loves her offspring and the wolf fights for her whelps, what can man say when he disregards the command6 and debases his nature, or when a son dishonors the old age of his father, or a father through a second marriage neglects the children of his first?7

The fact, then, that we were not taught by books what was useful is not a sufficient defense for us, who have understood how to choose what is advantageous by the untaught law of nature11

Yet, it is not possible for one, intelligently examining himself, to learn to know God better from the heavens and earth than from our own constitution, as the prophet says: 'Thy knowledge is become wonderful from myself'13

Aesop and Bidpai in Europe

I was originally going to post this as a reply, but it got pretty long and I felt it might as well be its own post.

While we're thinking about Aesop, a second cycle of animal fables were also making the rounds in Europe and were also quite popular, from the Middle Ages to the 19th century. In Europe, the were largely known as the Fables of Bidpai. Looking at their history might provide an interesting comparand to illustrate how these tales moved and circulated from place to place.

The fables are traceable back to India, where they were known as the Pañcatantra. They date as far back as the 3rd century BCE, roughly corresponding to the time of Alexander the Great. By 570 CE, they had been translated into Pahlavi Persian and were well-established in the court literature of the Sassanian Empire under the title Kalilag o Damnag, the names of the two jackals who are the central characters of the cycle, from their Sanskrit originals Karataka and Damanaka. Following the Arab conquest, the Zoroastrian convert Ibn al-Muqaffaʿ (d. 756) translated these fables from Pahlavi into literary Arabic as Kalilah wa-Dimnah. This edition of the text infused the ancient stories with one of the highest examples of literary Arabic style in existence (they are still studied today as examples of first-class writing) and introduced a number of new tales that soften the Buddhist element of the original stories and introduce some of his local Persian-Islamic sensibilities (although it has to be said that he is known as an excellent translator and did not shy away from controversial subjects, so we cannot accuse him of bowdlerizing the text). At the same time, there was a second original translation from the Pahlavi into Syriac, again around 550 CE, but this edition was left childless.

From the Arabic text of Ibn al-Muqaffaʿ, we have a Greek edition by Symeon Seth (c. 1080), which was then translated into Old Slavonic and Italian (1583), a modern Persian edition (c. 1120) that became the basis for the Ottoman Turkish translation, which was then translated into French by Galland (1724) and Cardonne (1778), a Hebrew edition (c. 1270) that was translated by John of Capua into Latin as the Directorium, which then became the basis for German (1480), Spanish (1493), and Italian (1552) branches. The German branch was rendered into Dutch and Danish in the 17th century, the Spanish was translated into Italian as Discorsi degli animali in 1548, and the Italian 1552 branch was translated into English by Sir Thomas North in 1570 as The Morall Philosophie of Doni: drawne out of the auncient writers. Many of these editions took the name Fables of Bidpai, after the Brahman philosopher Baidaba (Bidpai, Pilpai) who is the advisor to the new Indian monarch after Alexander's deposition of Porus (Fur), back in the 3rd century BCE. Finally—gotta love the Andalusian element—the Arabic edition was also directly translated into Spanish (1251), and then translated back into Latin by Raimond de Beziers. Meanwhile, a Latin poetic imitation of the cycle, Baldo's Alter Æsopus, was circulating as well.

Another case study of animal stories in circulation is the story of "The Case of the Animals versus Man," a long epistle-satire written in the style of a fable by the Brethren of Purity (Ikhwan al-Safaʾ) in the 970s. The text was copied from Arabic into Latin and Hebrew, one by Rabbi Joel and the other by Rabbi Jacob ben Elazar around 1240. Then, in 1316, it was translated again into Hebrew by Kalonymos ben Kalonymos, who incidentally also translates "Kalilah wa-Dimnah" and the works of Averroës into the same language. This Hebrew edition was printed in Warsaw in 1879, from which Yiddish and German translations were published. In addition, the Arabic had also been translated into Urdu, and then at the insistence of Abraham Lockett, a British official in colonial India, the Urdu text was translated into English! Thus, we have two totally different branches of the text meeting in Northern Europe, one through medieval Spain, one through India.

Given this daunting history of translation and re-translation, one can imagine that these tales might have been experienced in successive waves by any particular populace. Perhaps a man living in 14th century Provence would have heard the Fables of Bidpai orally from a Spanish Jew, who had read the Hebrew; perhaps his grandson read a Latin translation while at university; perhaps his grandson's grandson goes to Venice and hears the same stories in Italian; and perhaps, generations later, a descendant of theirs, seized by the wave of Egyptomania that swept the country following Napoleon's invasion, picks up a new French translation of the Ottoman Turkish Anwari Suhaili, "Lights of Canopus", and discovers the whole thing all over again, except where the word "God" appeared in the old Latin edition nobody read anymore, will now read "Allah" and imagine the stories taking place in the exotic locales of the East. I'm getting romantic here, but I think what these case studies might help us with is imagining how the stories of Aesop, Bidpai, and countless other bodies of lore that exist both orally and in written form could have been experienced and transmitted by people in the past.

References:

Keith-Falconer, I.G.N. Kalilah and Dimnah, or, The Fables of Bidpai : An English Translation of the Later Syriac Version after the Text Originally Edited by William Wright, with Critical Notes and Variant Readings. Amsterdam: Philo Press, 1970

Goodman, Lenn E. “Reading The Case of the Animals Versus Man: Fable and Philosophy in the Essays of the Ikhwān al-Ṣafāʾ.” In Epistles of the Brethren of Purity: the Ikhwān al-Ṣafāʾ and their Rasāʾil, edited by Nader El-Bizri, 248–274. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2008